A project in response to SpaceApps COVID-19 Challenge: A New Perspective

Noise around us

Are birds louder these days? Turns out so many people noticed this, that it started to reflect in web search trends.

One possible explanation is the lower overall noise level in cities and beyond (see also: The Quiet Planet challenge.) We asked ourselves:

Would a similar thing also happen under the sea?

Noise pollution in the time of pandemic

Noise pollution has been a growing concern among marine biologists. Increase in maritime traffic for both leisure and fishing purposes, military activity, offshore drilling are just a few examples of sources of unwanted sounds affecting some marine mammals, which depend on mechanisms like echolocation. Our understanding of the complex relation between our loud activities and ocean life is yet to be expanded. However, the present times posed a unique opportunity to research an acute drop in human racket.

As part of safety precautions during the COVID-19 pandemic, many coastal areas declared suspension of all non-essential maritime traffic. This has had a number of effects: the diminished number of traveling vessels leads to reduced noise pollution, decreases water turbidity as seen in Venice, but also limits the capability of marine biologists to perform measurement activities. Is the data out there ready to prove the link?

Maritime traffic

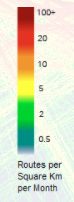

We investigated the maritime traffic. While AIS data is abundant online, many of the sources do not meet the criteria of openness while some others not yet provide the timeframes required for accurate determination of the changes as results of restrictions caused by the pandemic.

One of the sources that presents the ongoing changes in the maritime traffic can be found at [12]. Comparison of vessels and route density in March 2020 with the same period last year shows a significant reduction in human activity on the European waters. The same source reports a drop in fishing activities by nearly 40% on Western Mediterrean Sea, compared to the previous year.

One can hypothesize this leads to an equivalent reduction in sea water parameters like turbidity and noise pollution. However, we have not obtained the data to sufficiently prove the link as those were not yet available for the required timeframe.

Digital recognition of marine mammals

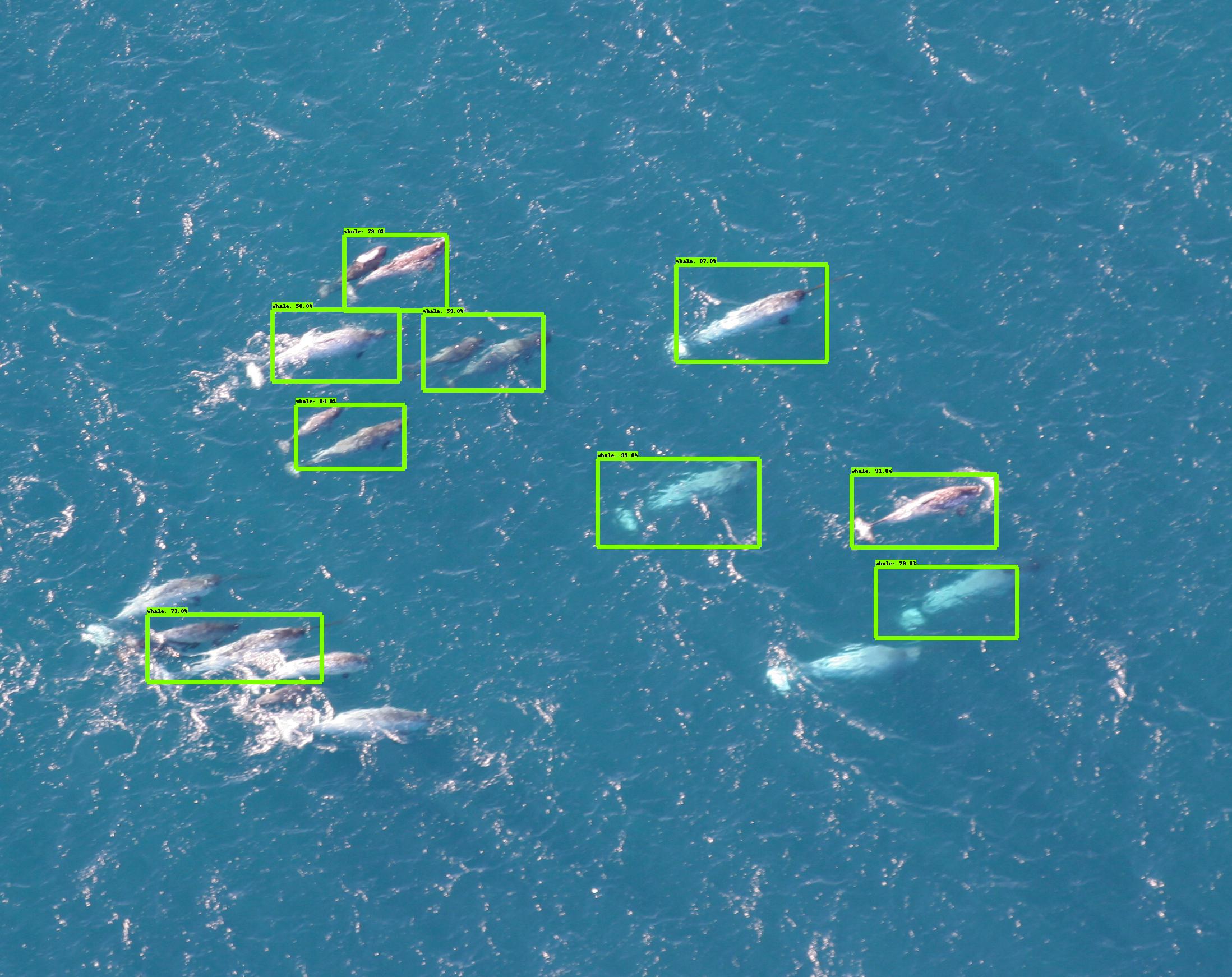

We created a whale detection engine, based on the paper released as a part of ESA’s project SPACE WHALE. A Convolution Neural Network (CNN) was trained to recognize cetaceans on the satellite and aerial pictures. Training pictures containing whales were obtained from [17].

Enclosed below is a snippet from the training process output. Diminishing loss value can be observed:

INFO:tensorflow:loss = 15.694896, step = 0

I0531 16:03:02.523565 140498314856320 basic_session_run_hooks.py:262] loss = 15.694896, step = 0

INFO:tensorflow:global_step/sec: 0.406591

I0531 16:07:08.469161 140498314856320 basic_session_run_hooks.py:692] global_step/sec: 0.406591

INFO:tensorflow:loss = 5.306469, step = 100 (246.082 sec)

I0531 16:07:08.604288 140498314856320 basic_session_run_hooks.py:260] loss = 5.306469, step = 100 (246.082 sec)

INFO:tensorflow:global_step/sec: 0.409948

I0531 16:11:12.402760 140498314856320 basic_session_run_hooks.py:692] global_step/sec: 0.409948

INFO:tensorflow:loss = 3.683988, step = 200 (243.800 sec)

I0531 16:11:12.404425 140498314856320 basic_session_run_hooks.py:260] loss = 3.683988, step = 200 (243.800 sec)

INFO:tensorflow:Saving checkpoints for 240 into /tmp/tmpeelow2fh/model.ckpt.

Such a neural network can be subsequently used on two sets of test aerial images, taken at different points in time, in order to compare number of animal occurences in some specific areas.

Code for the neural network can be found in the project repository.

Conclusions

- The pandemic impacts also the marine life, in multiple ways

- The reduced capacity of performing manual data gathering activities during pandemic restrictions can be offset by automation efforts, with the help of AI and remote sensing

- Aerial photography can be successfully used to detect cetaceans on ocean surface

Into the future

This is just a small glimpse of the possible areas for investigation. If the data from February to May 2020 could be obtained from regular hydrophone measurements and GPS trackers of cetacean specimen, more knowledge could be inferred about the response of the aquatic life to the sudden change in human activity. Combining with even more sources, like data from the WhaleWatch project, may yield even more interesting results.

References

ESA resources:

- [1] Project SPACE WHALE

- [2] A. Borowicz et al., Aerial-trained deep learning networks for surveying cetaceans from satellite imagery*

COVID-19 impact:

- [3] Quiet oceans: Has the COVID-19 crisis reduced noise in whale habitats?

- [4] Ocean Sound in COVID-19 Era

Noise affecting marine mammals:

- [5] Behavioral Changes Tutorial at Discovery of Sound in the Sea

- [6] R.M. Rolland et al., Evidence that ship noise increases stress in right whales

- [7] Listening To The Sea: Using Passive Acoustic Data to Monitor Ships and Ocean Life

- [8] S. Veirs et al., Ship noise extends to frequencies used for echolocation by endangered killer whales

- [9] Beluga Mother and Calf Communication | Notes From The Field | Ocean Wise (YouTube)

Maritime traffic:

- [10] Vessel ID System

- [11] National Ocean Service: What is ocean noise?

- [12] COVID-19 impact on fishing

Marine mammal presence detection:

- [13] E. Guirado et al., Whale counting in satellite and aerial images with deep learning

- [14] NOAA Kaggle Challenge: Right Whale Recognition

- [15] BelugaSounds: Using machine learning to detect beluga whale calls in hydrophone recordings

- [16] WhaleWatch program

- [17] NOAA photo library

- [18] Tensorflow detection model zoo

* the paper is an outcome of the SPACE WHALE project funded by ESA.